The Ottoman palace functioned as a space where grace and symbolism were intricately intertwined. Palace women were not only members of the royal family but also carriers of aesthetic sensibility, refined manners, and cultural sophistication. Their posture, attire, and gaze in portraits served as visual manifestos that reflected nobility, social status, and inner discipline.

Listen to the artwork in English.

Eseri Türkçe dinleyin.

In daily rituals, simplicity and elegance coexisted harmoniously. The hookah, in particular, was not merely a smoking device but a medium for conversation and a ritual of refinement in the social lives of palace women. The silently drifting smoke accompanied moments when time seemed to slow and glances replaced words.

Hookah culture in the Ottoman context was more than a smoking habit; it was part of an aesthetic whole. Each component—such as the bowl, hose, and base—was crafted with care, often adorned with glass and silver ornamentation, showcasing artisanal value. As much as the quality of the tobacco mattered, the grace and demeanor of the person serving it were equally significant. Shared quietly within the silk-draped rooms or inner gardens of the harem, the hookah became a silent ritual that reinforced trust, friendship, and elegance

The fan was both functional and symbolic. Beyond its practical purpose of cooling, it subtly directed body language and facilitated a form of mysterious communication. Draped in fine fabrics and embellished with embroidery, these fans silently yet powerfully conveyed femininity, grace, and social distance.

Altogether, these elements reveal that in the Ottoman palace, women were not merely visible figures but representations of an identity integrated with aesthetics. Beauty was complemented by demeanor; power by elegance.

Ottoman princesses, known by the title “Hanım Sultan,” were the daughters and granddaughters of the sultans. From birth, they received a privileged education and were raised in the refined environment of the imperial palace. Beauty, grace, education, and knowledge of politics were among their defining qualities.

Listen to the artwork in English.

Eseri Türkçe dinleyin.

They were trained in the Qur’an, literature, calligraphy, music, foreign languages, and the etiquette of the Ottoman court. Many princesses with a passion for classical Ottoman poetry (divan edebiyatı) composed poems and letters. Although they did not directly participate in state governance, they often influenced palace politics indirectly through their fathers, brothers, or husbands. Particularly, those with close ties to the valide sultan (queen mother) or the grand viziers could hold significant political influence.

Marriage and Diplomacy: Ottoman princesses were usually married to high-ranking pashas, grand viziers, or provincial governors. These marriages were strategic, aimed at strengthening political alliances and ensuring loyalty. After marriage, they often held considerable influence in the palaces where they lived. Many princesses were also known for their philanthropy, founding charitable foundations (vakıfs) and commissioning mosques, madrasahs, fountains, and hospitals. Figures such as Mihrimah Sultan, Fatma Sultan, and Esma Sultan are remembered for their remarkable charitable works.

Fashion and Style: Ottoman princesses wore elegant kaftans, silk garments, and jewelry adorned with precious stones, often setting trends in fashion and art within the court.

While Ottoman princesses did not directly govern, they played vital roles in cultural, diplomatic, and social life, leaving a lasting impact on Ottoman society.

Tobacco entered the Ottoman Empire around 1601–1602, approximately 110 years after the discovery of the Americas. Initially, only imported tobacco was taxed; however, as the number of users increased, some religious scholars issued fatwas against its consumption. Tobacco bans were enforced during the reign of Sultan Ahmed I but were later relaxed under Sultans Mustafa I and Osman II.

Listen to the artwork in English.

Eseri Türkçe dinleyin.

In the Ottoman Empire, müzeyyen (ornamented) and murassa (jeweled) fans were refined symbols of elegance, prestige, and exquisite craftsmanship. Adorned with masterful enamel work, these fans were typically crafted from silver and embellished with precious or semi-precious stones. Their fan sections were often made from ostrich feathers, with ornate motifs at the center.

Listen to the artwork in English.

Eseri Türkçe dinleyin.

The art of fan-making emerged in the early Ottoman period. Renowned masters included A’rec (Topal) Ömür Usta of Kasımpaşa, Hazerfen Ali Efendi, and Müezzinzade Salih Efendi. According to historical sources, there were four main types of fans in Ottoman culture. Among them, those with jeweled centers, murassa handles, and white bird feathers were made specifically for the imperial palace (Saray-ı Hümayun) and high-ranking members of the court.

In the Ottoman court, fans were not only tools for cooling but also conveyed grace, social standing, and even secret communication. Large feathered fans were carried by attendants to cool the sultans, while smaller, folding fans served as elegant personal accessories for palace women.

These fans—often adorned with gold, silver, ivory, and gemstones—were intricately crafted by jewelers and woodcarvers, merging fine art with artisanry. They also served as discreet communication tools in social settings and theatrical performances.

Today, Ottoman palace fans are exhibited in museums, preserving and reflecting this delicate aspect of cultural heritage.

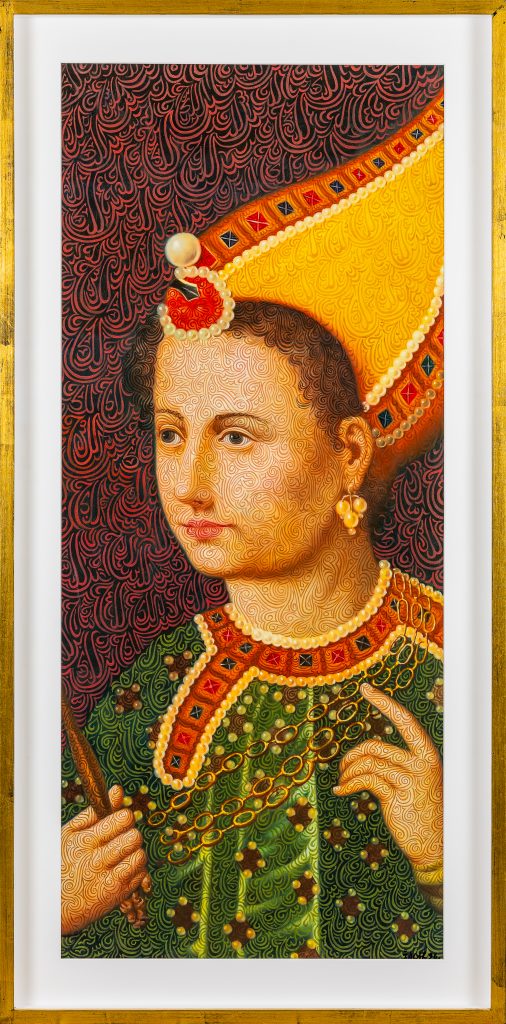

Calligraphic Portrait

This calligraphic portrait depicts Hurrem Sultan. Born Roxolana, also known as Anastasia/Aleksandra Lisowska, she was of Polish (present-day Ukrainian) origin. She was the wife of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent and the first woman in Ottoman history to officially hold the title of Haseki Sultan. Her rise marked the beginning of the era known as the “Sultanate of Women.”

Hurrem Sultan played an influential role in state affairs. Through her power in the palace, she shaped not only the order of the imperial harem but also external politics. She is particularly remembered for her involvement in the dismissal of Grand Vizier Ibrahim Pasha.

Listen to the artwork in English.

Eseri Türkçe dinleyin.